Twin Peaks Pilot

Unraveling the Dualities: A Profound Exploration of Motifs, Parallel Themes, and Psychological Challenges in Twin Peaks Pilot

Unraveling the Dualities: A Profound Exploration of Motifs, Parallel Themes, and Psychological Challenges in Twin Peaks Pilot

The pilot episode of Twin Peaks introduces viewers to a world where the boundaries between the real and the surreal blur, creating a space where desire, power, and the psyche intertwine. The pilot episode sets the stage for a deeper exploration of identity, power, and the interplay between the conscious and unconscious minds. Central to this episode is the way characters navigate their desires and the dark, often hidden, aspects of their personalities.

The Whimsical and the Dark: Audrey Horne's Dance of Desire

Audrey Horne, one of the most enigmatic characters introduced in the pilot, embodies a complex interplay of innocence and eroticism, as well as a profound understanding of the darker undercurrents that run through the town of Twin Peaks. Audrey’s presence in the series is marked by a supernatural quality, as she seems to glide through the Great Northern Hotel like a ghost, slipping through secret passages and observing the world with a detachment that belies her age.

- Audrey as the Ghostly Seductress: Audrey’s movements and demeanor suggest a character who exists on the periphery of the world she inhabits, not fully grounded in the reality of Twin Peaks. She is a figure of desire, not just for others, but also as someone who manipulates and controls the desires of those around her. Her actions are not simply those of a rebellious teenager; they are calculated, as she uses her sexuality and her understanding of power dynamics to influence and control. Audrey's interactions, particularly in her pursuit of employment at her father’s department store, highlight her ability to navigate the intersection of desire and capital. She understands that these two forces are inextricably linked and uses this knowledge to her advantage, manipulating the manager with her charm and youthful allure to get what she wants. Audrey’s character represents a nexus of libidinal and economic forces, where desire is both a tool and a currency.

- The Intersection of Desire and Capital: The pilot subtly suggests that Audrey is aware of the town’s darker secrets, including the illicit activities at One-Eyed Jacks. Her behavior in the department store interview, where she capitalizes on the manager’s thinly veiled sexualization of her, demonstrates her understanding that the circulation of capital and desire are intimately connected. Audrey’s actions are not just about getting a job; they are about asserting control over a system that seeks to objectify her. By playing into the manager’s desires, she manipulates the power dynamics to her favor, showcasing her ability to command the libidinal energies that drive much of the town’s underbelly. Audrey's character, in many ways, mirrors the mystic presence of Agent Cooper, yet where Cooper commands the occult and the mystical, Audrey wields her power in the realms of desire and sexuality.

The Familial and the Erotic: Bobby Briggs and Domestic Chaos

Bobby Briggs, in contrast to Audrey, represents the chaos and danger that arise when desire is unchecked and unchanneled. Where Audrey is calculated and controlled, Bobby is impulsive and reckless, embodying a raw, unfiltered energy that threatens to destabilize the fragile social order of Twin Peaks.

- Bobby’s Dangerous Charisma: Bobby is a classic "bad boy" archetype, but with a depth that makes him both fascinating and terrifying. He is not merely rebellious; he is a figure of genuine danger, involved in violent and criminal activities that reflect his chaotic inner world. Unlike James Hurley, who is often portrayed as the "sad boy" with a veneer of rebellion, Bobby is truly unpredictable, and his presence in any situation introduces a potential for violence and disruption. Bobby's involvement with Shelly and Leo’s domestic life further complicates his character. He inserts himself into their toxic marriage, not just as a lover, but as an agent of destruction, bringing with him the potential for both liberation and further chaos.

- The Cuckolding and the Gun: The scene in which Bobby interacts with Shelly, particularly around the gun, is rich with psychoanalytic symbolism. The gun represents both phallic power and the underlying threat of violence that defines Bobby’s relationship with Shelly and Leo. By entering into this domestic space, Bobby disrupts the established power dynamic, positioning himself as both a savior and a threat. His relationship with Shelly is not merely an affair; it is an attempt to dismantle the oppressive structure of her marriage to Leo, using the very tools of violence and dominance that Leo himself wields. Yet, Bobby's reckless nature suggests that he is not entirely in control of the forces he unleashes, making him as dangerous to Shelly as Leo is. The gun, therefore, is a symbol of the fragile balance of power in this love triangle, where desire, violence, and control intersect in a deadly dance.

The Mystic and the Material: Agent Cooper and the Dreamworld

Agent Dale Cooper, introduced in the pilot as the FBI agent sent to investigate Laura Palmer’s murder, brings with him a mystical presence that contrasts sharply with the material realities of the town. Cooper’s character embodies the intersection of the conscious and unconscious minds, where dreams and intuition play as much a role in his investigations as logic and evidence.

- Cooper as the Mystic: Cooper’s approach to solving the mystery of Laura Palmer’s death is marked by his reliance on dreams, symbols, and intuition. His character is deeply connected to the idea that there are forces at work in Twin Peaks that transcend the material world, and he is uniquely equipped to navigate these forces. Cooper’s connection to the dreamworld is highlighted by his interactions with the Log Lady, whose cryptic statements about fire and the devil suggest a deeper, more mystical understanding of the events unfolding in the town. Cooper’s ability to interpret these symbols and integrate them into his investigation underscores his role as a conduit between the physical and metaphysical realms. This positions him as the counterbalance to characters like Audrey and Bobby, who operate within the material world of desire and power.

- The Dream as a Guide: In the pilot, Cooper’s first interactions with the residents of Twin Peaks, particularly with Sheriff Truman and the Log Lady, establish his role as a figure who sees beyond the surface. His dreamlike approach to investigation, where he places as much importance on a feeling or a hunch as he does on physical evidence, sets the tone for the series’ exploration of the unconscious mind. The integration of the dreamworld into the narrative reflects the show’s broader theme of duality, where the conscious and unconscious, the material and the mystical, are constantly intersecting. Cooper’s character is the embodiment of this intersection, navigating the town’s mysteries with a blend of rationality and intuition that challenges traditional methods of investigation.

The Tragedy of Leland Palmer: Social Decorum and the Unraveling Psyche

Leland Palmer’s character in the pilot is one of the most tragic, as he grapples with the immediate aftermath of his daughter Laura’s murder. Leland’s breakdown, particularly his public displays of grief, reveal the tensions between social expectations and the raw, uncontainable emotions that come with such a profound loss.

- Leland as the Gothic Heroine: Leland’s public breakdowns, especially his desperate dancing at the Great Northern, cast him in the role of the gothic heroine—a figure overwhelmed by emotion in a world that demands restraint. His grief is treated by those around him as an embarrassment, something to be hidden away rather than acknowledged and integrated into the community’s response to tragedy. Leland’s character challenges the town’s obsession with maintaining social decorum, revealing the cracks in the veneer of respectability that masks the town’s darker secrets. His grief, though deeply personal, is also a social problem, one that the town is ill-equipped to handle. The lack of empathy and support Leland receives highlights the isolation that often accompanies intense grief, where the individual’s emotional reality is at odds with societal expectations.

- The Social Veneer and the Psychedelic Vortex: Leland’s breakdowns are not just personal tragedies; they are moments where the social veneer of Twin Peaks is stripped away, revealing the "psychedelic vortex" of violence and desire that underpins the town’s seemingly peaceful existence. Leland’s grief, when expressed publicly, becomes a threat to the town’s social order, forcing the residents to confront the uncomfortable truth that their world is built on a foundation of repression and denial. The reaction to Leland’s grief, where he is encouraged to hide his emotions and return to "normal," reflects the town’s collective fear of what lies beneath the surface. Leland’s character becomes a symbol of the dangers of repression, where the refusal to acknowledge and integrate trauma leads to a disintegration of the self.

The Psychology and Sociology of Melodramatic Relationships in Twin Peaks

Twin Peaks, created by David Lynch and Mark Frost, is a masterclass in blending the surreal with the mundane, all within the confines of a small-town mystery. But beneath its bizarre imagery and cryptic dialogues lies a rich exploration of melodramatic relationships, both psychological and sociological. These relationships are not just plot devices but are integral to understanding the deeper emotional currents of the show.

Melodrama as the Core of Twin Peaks

At its heart, Twin Peaks is a melodrama, steeped in the traditions of soap operas and other serialized storytelling. The show’s central plot, the murder of Laura Palmer, serves as a classic MacGuffin—an excuse to delve into the tangled lives of the town’s residents. The melodramatic relationships are the lifeblood of the narrative, with characters constantly engaged in secret affairs, betrayals, and emotional turmoil. This is classic soap opera territory, where personal relationships are heightened to the point of absurdity, yet remain eerily relatable.

Psychological Dimensions of Melodramatic Relationships

Psychologically, the relationships in Twin Peaks are a study in extremes. Characters like Laura Palmer embody the duality of human nature—innocent and pure on the surface, but deeply troubled and corrupted underneath. Her relationships with figures like James Hurley and Bobby Briggs are emblematic of her inner conflict, as she oscillates between love, fear, and self-destruction. This duality is not just limited to Laura; it permeates the entire town, where every relationship seems to hide a darker truth beneath its surface.

Dale Cooper, the show’s enigmatic protagonist, brings a different psychological layer to the melodrama. His relationship with the town, especially with characters like Audrey Horne and Sheriff Harry S. Truman, is one of mutual respect and unspoken understanding. Yet, Cooper’s psychological state is marked by his obsession with the metaphysical and his constant battle with his own demons, which is reflected in his dreams and visions. These psychological underpinnings add depth to the melodramatic relationships, making them more than just surface-level interactions.

Sociological Implications of Melodramatic Relationships

From a sociological perspective, Twin Peaks examines how these melodramatic relationships are shaped by and reflect the social structures of the town. The Palmer family, for instance, represents the town’s idealized image of the American family—successful, respected, and seemingly perfect. However, the dysfunction within the Palmer household, hidden from public view, mirrors the societal tendency to maintain appearances at all costs. This façade is a recurring theme in Twin Peaks, where characters are often trapped by the roles they are expected to play in society, whether it’s as a dutiful spouse, a loyal friend, or a model citizen.

The town of Twin Peaks itself is a microcosm of American society, with its inhabitants representing various social archetypes. The relationships between these characters—whether romantic, familial, or platonic—are often dictated by these social roles. For instance, the affair between Norma Jennings and Big Ed Hurley is constrained by their respective marriages, which are themselves reflections of societal expectations. The melodramatic nature of these relationships highlights the tension between personal desires and social obligations, a tension that is at the core of the show’s narrative.

The Wild Woods of Twin Peaks

Twin Peaks resists easy interpretation, much like the dense, untamed woods that surround the town. Its melodramatic relationships are not meant to be neatly dissected or solved but experienced in their full, messy glory. The psychology and sociology of these relationships are deeply intertwined, creating a complex web that reflects the show’s broader themes of duality, secrecy, and the conflict between appearance and reality.

In the end, Twin Peaks invites us to become part of its world, to get lost in its woods, and to explore the wild, uncharted territory of its characters’ lives. As viewers, we are not just passive observers but cohabitants of this strange town, participating in its dramas, sharing in its secrets, and ultimately, finding our own reflections in its melodramatic relationships.

Motifs and Symbolism in Twin Peaks

One of the most compelling elements of Twin Peaks is its use of motifs and symbolism, which contribute to its surreal atmosphere and deepen its exploration of melodramatic relationships. These motifs often serve as psychological statements, revealing the inner workings of characters and the broader themes of the show.

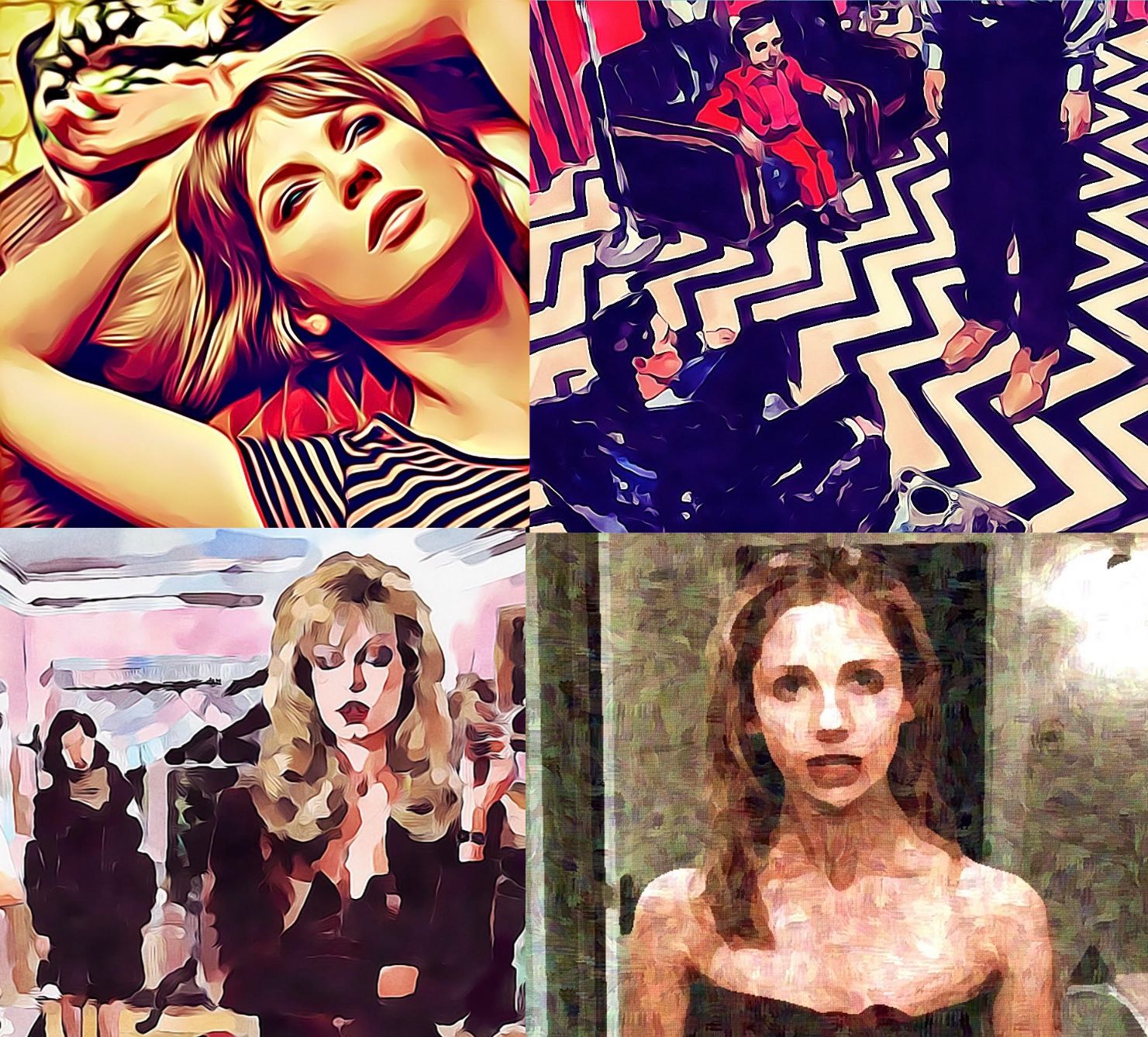

The Red Room: A Portal to the Unconscious

Perhaps the most iconic motif in Twin Peaks is the Red Room, a surreal, otherworldly space that exists beyond the physical realm. The Red Room, with its red curtains, chevron-patterned floor, and enigmatic characters like the Man from Another Place, functions as a portal to the unconscious mind. It is a place where the boundaries between reality and dreams blur, and where characters confront their deepest fears and desires.

Psychologically, the Red Room represents the hidden aspects of the psyche, the parts of ourselves that we often repress or ignore. For Dale Cooper, the Red Room is a space where he must confront the duality within himself—the battle between his desire for justice and the darker impulses that threaten to consume him. The Red Room’s cryptic messages and bizarre imagery underscore the idea that the human mind is not easily understood or controlled. It is a place of both revelation and confusion, where truth is obscured by layers of symbolism.

The Black Lodge and the Duality of Good and Evil

Closely related to the Red Room is the Black Lodge, a dimension that embodies pure evil. The Black Lodge is the source of malevolent forces in Twin Peaks, and its influence is felt throughout the town. The concept of the Black Lodge introduces a metaphysical dimension to the show’s exploration of good and evil, suggesting that these forces are not just abstract concepts but tangible entities that can influence and corrupt individuals.

The duality of the White Lodge (representing good) and the Black Lodge (representing evil) mirrors the duality present in the characters of Twin Peaks. This duality is most evident in the character of Laura Palmer, who is both a victim and a perpetrator, embodying both innocence and corruption. The Lodges serve as a metaphor for the internal struggle between these opposing forces, a struggle that every character in Twin Peaks faces to some degree.

Psychological Statements Through Visual Metaphors

Twin Peaks is rich with visual metaphors that offer psychological insights into its characters. One such metaphor is the use of mirrors, which appear frequently throughout the series. Mirrors in Twin Peaks often signify a moment of self-reflection or the revelation of a hidden truth. For example, Leland Palmer’s encounters with mirrors often coincide with the emergence of his darker, murderous alter ego, BOB. The mirror becomes a symbol of the fractured self, reflecting the inner conflict between Leland’s public persona and the evil that resides within him.

Another powerful visual metaphor is the recurring motif of fire. Fire in Twin Peaks is both destructive and purifying, symbolizing the potential for both harm and renewal. The phrase “Fire walk with me” is a chilling invocation of the destructive power of fire, but it also hints at the idea of confronting and overcoming one’s inner demons. Fire’s dual nature as both a force of creation and destruction parallels the duality of the characters in Twin Peaks, who are often torn between their better instincts and their darker impulses.

The Role of Dreams and the Subconscious

Dreams play a central role in Twin Peaks, serving as a conduit for the subconscious mind to communicate with the conscious world. Dale Cooper’s dreams are particularly significant, often providing cryptic clues that help him unravel the mystery of Laura Palmer’s death. These dreams are not merely random occurrences but are deeply tied to the psychological and emotional states of the characters.

The dream sequences in Twin Peaks often blur the line between reality and fantasy, reflecting the show’s exploration of the unconscious mind. In these dreams, time and space are fluid, and characters can encounter past, present, and future selves. The surreal imagery and disjointed narratives of these dreams echo the complexity of the human mind, where memories, fears, and desires intermingle in ways that defy logic.

The use of dreams in Twin Peaks also speaks to the idea that understanding the human psyche requires looking beyond the surface. The show suggests that the truth about ourselves and others is often buried in the subconscious, accessible only through dreams or moments of heightened emotional intensity. This emphasis on the subconscious as a key to understanding the self aligns with Lynch’s broader interest in psychoanalysis and the mysteries of the mind.

The Psychological Landscape of Twin Peaks

The town of Twin Peaks itself can be seen as a psychological landscape, where the physical environment mirrors the inner turmoil of its inhabitants. The dense, mysterious woods that surround the town are a recurring motif, symbolizing the unknown and the unknowable. These woods are both a refuge and a place of danger, where secrets are buried and where the boundary between the natural and supernatural blurs.

The town’s isolation, nestled in the Pacific Northwest, also contributes to its psychological atmosphere. Twin Peaks is a place where time seems to stand still, where the past continually haunts the present. This temporal dislocation creates a sense of unease, as if the town exists in a liminal space between reality and fantasy. This setting amplifies the melodramatic relationships within the town, where every interaction is charged with emotional intensity, and where the ordinary is tinged with the extraordinary.

The Complex Semiotics of Coffee in Twin Peaks

In Twin Peaks, coffee is more than just a morning ritual or a simple beverage—it is a symbol deeply intertwined with the show’s narrative, characters, and themes. The presence of coffee, especially within the context of law enforcement, operates on multiple levels, serving as both a cultural signifier and a thematic device. This complex semiotics of coffee reveals much about the epistemological commitments of the show and its characters.

In American culture, coffee and donuts are almost inseparable from the image of law enforcement. This association is not just a cliché but a deeply ingrained symbol of the routine and mundanity that characterize the everyday lives of police officers. However, in Twin Peaks, this mundane symbol takes on a richer, more layered significance. Coffee, for instance, becomes a conduit through which the characters’ relationships and the show’s larger themes are explored.

One of the key scenes that encapsulates this is when Andy, one of the deputies in the town, becomes emotionally overwhelmed upon discovering Laura Palmer’s body. Andy’s tears, his inability to suppress his emotions, contrast sharply with the sheriff’s more traditional, stoic response. This scene uses the semiotics of coffee and donuts—the archetypal symbols of police work—to subvert expectations. Instead of reinforcing the stereotype of the unemotional, tough cop, Twin Peaks presents a character who defies this archetype through his vulnerability.

Subverting Patriarchal Masculinity

Andy’s emotional response is not just a moment of comic relief or an anomaly within the show’s depiction of law enforcement; it is a deliberate subversion of patriarchal masculinity. In a profession often depicted as requiring emotional detachment, Andy’s tears challenge the notion that men, especially those in traditionally masculine roles, must suppress their emotions to be effective. This subversion is significant because it opens up a conversation about the emotional lives of men within the framework of patriarchal expectations.

In this context, the sheriff’s admonition for Andy to "man up" can be seen as an attempt to reinforce these traditional expectations. However, the show’s framing of Andy as a sympathetic character, someone with whom the audience can identify, subtly undermines this. By aligning the viewer’s sympathies with Andy, Twin Peaks encourages a rethinking of what it means to be a man in a patriarchal society. Instead of seeing Andy as defective or weak, the show positions him as someone who is perhaps more in touch with his humanity than his more emotionally repressed counterparts.

This moment of vulnerability in Andy, set against the backdrop of a stereotypical police procedural, underscores Twin Peaks’s commitment to exploring the emotional and psychological depths of its characters. The show’s willingness to subvert these stereotypes is part of what makes it a rich text for analysis, particularly from a feminist perspective.

Approaching Twin Peaks from a Feminist Perspective

The depiction of Laura Palmer, the quintessential beautiful, blonde, blue-eyed American girl, is central to the feminist critique of Twin Peaks. The show’s focus on the death of a young woman as its central mystery brings to mind Edgar Allan Poe’s infamous assertion that the death of a beautiful woman is the most poetic subject. This trope, common in many police procedurals, often reduces women to mere plot devices, their suffering serving as a catalyst for the (usually male) protagonist’s journey.

However, Twin Peaks complicates this trope in several important ways. While Laura Palmer’s death is the event that sets the narrative in motion, the show is less interested in her as a victim and more concerned with her as a complex, multifaceted character. Through flashbacks, dreams, and the testimonies of those who knew her, Laura is portrayed as a young woman with her own agency, desires, and struggles. This portrayal challenges the reductionist view of women as mere objects of male desire or victims of male violence.

Moreover, the show’s treatment of gender is nuanced and often subversive. For instance, the character of Andy, with his open display of emotion, contrasts with the more traditionally masculine characters like the sheriff and Dale Cooper. This contrast invites viewers to question the societal norms that dictate how men and women should behave. Similarly, the show’s female characters, such as Audrey Horne and Donna Hayward, are given their own arcs and agency, further complicating the traditional gender dynamics of the genre.

David Lynch: A Feminist Filmmaker?

There is a strong argument to be made that David Lynch, despite some of the more dated aspects of his visual language, is a filmmaker who engages deeply with feminist themes. Lynch’s films often explore the psychological complexity of his female characters, presenting them as individuals with rich inner lives rather than mere symbols or objects. In Twin Peaks, this is evident in the way Laura Palmer is depicted not just as a victim, but as a person with her own narrative and agency.

Lynch’s interest in the “psychological multitude” within individuals, particularly women, sets his work apart from more straightforward narratives that rely on simplistic gender stereotypes. Unlike many noir and neo-noir films, which often reduce women to the role of the femme fatale, Twin Peaks presents its female characters as multifaceted and deeply human. This complexity is one of the reasons why Twin Peaks remains a subject of fascination and study, particularly within feminist discourse.

Conclusion: The Layers of Twin Peaks

Twin Peaks is a show that operates on multiple levels, blending the surreal with the mundane and the psychological with the sociological. Its exploration of melodramatic relationships, the complex semiotics of coffee, and its nuanced approach to gender make it a rich text for analysis. Whether viewed through a feminist lens, a psychological lens, or a sociological lens, Twin Peaks offers endless opportunities for interpretation and discussion.

As we continue to explore the world of Twin Peaks, it becomes clear that the show is not just a murder mystery or a soap opera, but a deep, multifaceted exploration of the human condition. Its characters, with their emotional complexity and rich inner lives, invite us to look beyond the surface and consider the deeper forces at play in their lives. In doing so, Twin Peaks challenges us to reflect on our own lives and the society in which we live, making it a truly timeless piece of art.

Conclusion: The Liminal Space of Twin Peaks

Twin Peaks is a show that resists easy categorization, blending elements of soap opera, police procedural, horror, and surrealism into a unique and unsettling experience. Its exploration of melodramatic relationships is enriched by its use of motifs, visual metaphors, and psychological statements, creating a complex web of meaning that invites multiple interpretations.

At its core, Twin Peaks is a meditation on the duality of human nature, the tension between good and evil, and the mysteries of the subconscious mind. Its characters are not merely participants in a melodrama but are embodiments of the psychological and sociological forces that shape our lives. As we navigate the strange, dreamlike world of Twin Peaks, we are reminded that the line between reality and fantasy, sanity and madness, is often thinner than we might like to believe.

Comments ()